Telomere tech to fight cancer

Scientists have found a new way to impair cancer cell growth.

Scientists have found a new way to impair cancer cell growth.

A team from Children’s Medical Research Institute (CMRI) says its research could lead to the development of a new class of cancer therapeutics with minimal side-effects on normal cells.

“This project builds on over a decade of work by my team and our collaborators to develop antiproliferative agents that target telomeres,” says Professor Hilda Pickett, who leads CMRI’s Telomere Length Regulation Unit.

“The results are promising and have future potential to improve long term health outcomes for all types of cancer.”

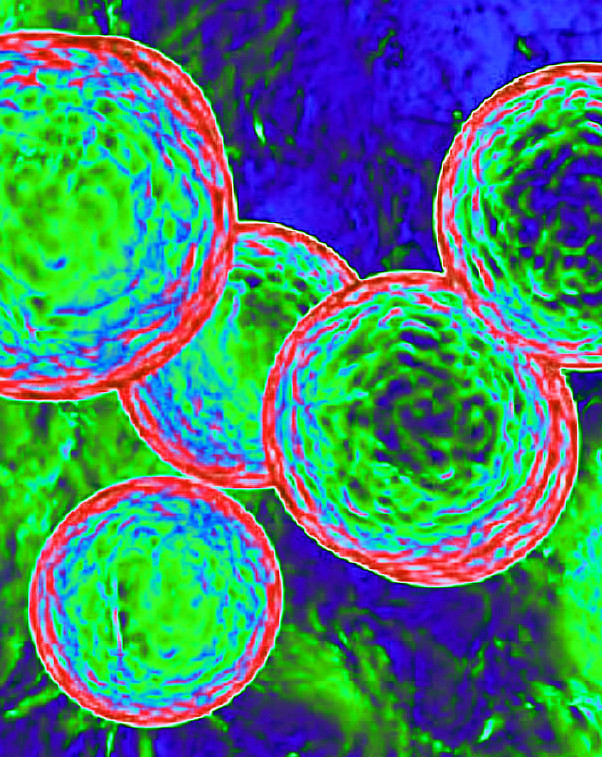

DNA is protected by telomeres, found at the ends of our chromosomes, which form a looped structure guarded by an array of proteins, with one of the most crucial being TRF2.

When this protective telomere structure is disrupted, there are catastrophic effects on cells, causing them to die.

Cancer cells exist on the edge of catastrophe. The unlimited proliferative capacity of cancer cells is entirely dependent upon telomere maintenance, making factors that control telomeres attractive chemotherapeutic targets.

Anything that tips them over the edge can selectively kill cancer cells without harming the normal cells in our body.

Unlike radiation and most chemotherapies, the side effects of telomere-focused cancer drugs are predicted to be much lower, improving patient survival and long-term outcomes.

CMRI’s Dr Alex Sobinoff, a member of Professor Pickett’s team, is lead author on a paper, published in Cell Chemical Biology, which describes the first compound to strongly bind a key region of TRF2.

This compound, called APOD53, impairs cell growth in cancer cells (using both known telomere maintenance mechanisms—ALT and telomerase), while sparing non-cancerous cells.

“These compounds represent fantastic new tools for fundamental research and prove that we can develop cancer therapeutics that specifically target TRF2,” Sobinoff says.

They have also shown the effectiveness of their new compound can be increased in combination with other chemicals affecting other parts of the protective structure on telomeres. Additionally, their compound, a peptide, is permeable, meaning it can easily enter cells and is thus a good candidate for future anti-cancer drug development.

Print

Print