Teeth let teams nibble at fossil information

Researchers have used advanced techniques to turn back the evolutionary clock.

Researchers have used advanced techniques to turn back the evolutionary clock.

The technique could make it much easier to go back through the evolutionary history of mammals using fossilised remains.

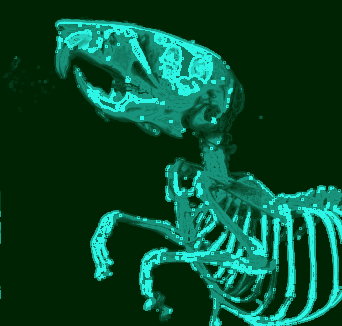

A new study saw biologists fine-tune the shape of a mouse tooth, to produce the gradual transitions observed in the fossil record.

The research is published in the journal Nature.

Biologists have long studied animals with gene mutations to discover ways that the fine details of teeth can shed light on the evolutionary relationships of extinct species, but the changes were often too dramatic to be very informative.

Now, an international collaboration involving Australian researchers has used laboratory experiments on developing teeth combined with computer simulations, to show for the first time how the processes of development influence the evolution of fine tooth features.

“If you want to reconstruct the tree of life of extinct animals, teeth are often the best or only evidence that palaeontologists have available,” Monash University researcher Dr Alistair Evans, from the School of Biological Sciences, said.

“Particularly for mammals, the fine features of teeth help us to determine how fossil species are related to each other and modern animals.”

“However, we have always been limited in what we can learn because many features of teeth are correlated when the embryo develops so they evolve together.

“Here we have been able to show how some of these correlations work,” Dr Evans said.

The research team traced the evolutionary steps of teeth by applying the protein of a mutant gene to the molars of mutant mice in the laboratory, which are simple cone-shaped cusps.

The protein was added in small, incremental steps to see if all features of the teeth change at the same time.

The experiments revealed that the cusps, the main features of teeth, reappeared with increasing amounts of protein, and in much the same order that cusps have evolved in early mammal molars.

In a second experiment, teeth were produced that look remarkably like those in the ancestors of rodents, matching the ones found in fossils.

“Amazingly, we found that the features that we could control in mice vary in the same way in carnivorous mammals like the lion, wolf, and bear - the same rules apply to cats and mice,” said Dr Evans.

The next phase of research will investigate other mechanisms that influence tooth development, and apply these results to more accurately reconstruct the history of mammals.

Print

Print