Single-cells seen to take unknown genetic initiative

Life thrives in the world’s harshest climates, and a recent report has shown a previously-unknown method some creatures use to reproduce in extreme situations.

Life thrives in the world’s harshest climates, and a recent report has shown a previously-unknown method some creatures use to reproduce in extreme situations.

A new study has revealed a family of single-celled organisms called archaea is able to sidestep normal replication processes, by avoiding a step that seemed fundamental.

Researchers at The University of Nottingham have found the archaea Haloferax volcanii not only does not need to copy its DNA to replicate itself – but by not doing so it grows more rapidly than organisms which do. The finding could shed some light on the mechanisms which allow cancerous cells, for example, to reproduce without complete genetic coding.

“We have shown that in some organisms, the replication origins — genetic switches that control DNA replication — are not only unnecessary but cells will actually grow faster when these origins are not present. This is totally unexpected and has forced us to re-evaluate one of the cornerstones of DNA biology,” said Dr Thorsten Allers from the University’s School of Life Sciences.

All life forms need to copy their DNA before the cell can divide and reproduce. Most creatures do this via a series of ‘replication origins’ located near their chromosomes and onto which proteins bind to start the replication process.

For humans and other eukaryotes, when these replication origins are eliminated a cell cannot reproduce, and will generally die.

But the new study has found that the Haloferax volcanii is able to start off chain reaction of replication all around its chromosomes, even when its replication origins are non-existent

The researchers also found that far from being disadvantaged by having to prompt its own reproduction, the archaea without chromosomal origins grew considerably faster.

“The amazing thing that we found wasn't just that deleting the origins still allowed the cells to grow, but that they now actually grew almost 10 per cent faster. Everybody was thinking, ‘where's the catch?’ But we haven't found one” Dr Conrad Nieduszynski said.

“The way cells initiates this replication process is to use a form of DNA repair that exists in all of us, but they just hijack this process for a different purpose. By using this mechanism, they kick-start replication at multiple sites around the chromosome at the same time.”

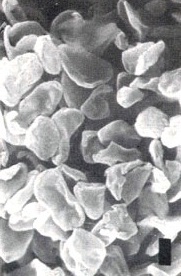

Achaea were quite recently discovered, living in extreme environments at very high or very low temperatures, as well as in highly salty, acidic or alkaline water. They are one of the three distinct subsets of life along with bacteria and eukaryotes, which are multi-celled organisms including humans, other animals, plants and fungi.

Genetically, archaea are more closely related to eukaryotes, and therefore humans, than to bacteria.

“Although they look like bacteria and behave like bacteria, archaea are actually more closely related to us. Where we really see the similarities is when we look at the enzymes that are responsible for DNA replication and that's why we thought this would be an interesting system to work on. We've got something that's life but not as we know it: on the outside they look like bacteria but on the inside they look like us,” Dr Allers said

“Scientists think that cancer cells revert back to a more primitive state without these forms of control. This is how they resemble Haloferax volcanii. One of the other hallmarks of cancer cells is that grow faster than ordinary cells and can quickly take over the body. This is similar to what we are seeing — when you don't regulate DNA replication and dispense with the normal checks and balances, you can have unregulated, faster growth.”

Full details are available from the report, published in the journal Nature.

Print

Print