Movement restored by spinal zaps

Six people with severe spinal cord injuries have regained the use of their hands and fingers through a non-invasive spinal stimulation technique.

Six people with severe spinal cord injuries have regained the use of their hands and fingers through a non-invasive spinal stimulation technique.

Scientists employed at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and UCLA used a new technique, a form of neuromodulation, to enable patients to turn doorknobs and open bottles for the first time since sustaining their injuries.

They say their findings represent the most extensive reported recovery of patients’ use of their hands.

“Spinal cord injury is devastating to patients and to their families, and it’s usually judged irreversible. This work by Professor Edgerton and his team is remarkable and unprecedented – for the first time, a quadriplegic has recovered hand function through transcutaneous (across the skin) stimulation,” said UTS researcher Professor Bryce Vissel.

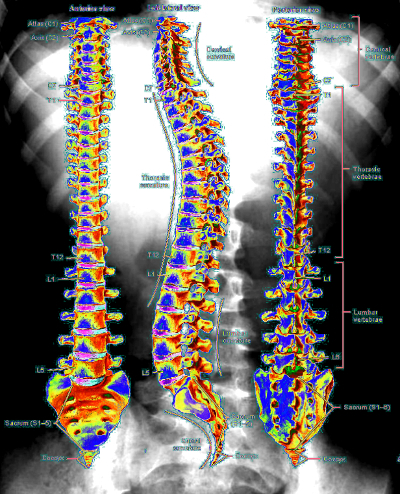

The research involves placing electrodes on the skin to stimulate the circuitry of the spinal cord. In this method of neuromodulation, called transcutaneous enabling motor control (tEmc), electrical currents are applied at varying frequencies and intensities to specific locations on the spinal cord. Patients also undertook intensive grip-strength training.

At the start of the study, three patients could not move their fingers at all, and none could turn a doorknob with one hand or twist the lid off a plastic water bottle. All had difficulty using a mobile phone.

“About midway through the sessions, I could open my bedroom door with my left hand for the first time since my injury,” said one research participant.

Within two to three sessions, everyone started to show significant improvements and kept progressing.

“In addition to regaining use of their fingers, the research subjects also gained other health benefits – better blood pressure, improved bladder and cardiovascular function, and the ability to sit upright without support,” UCLA research scientist Dr Parag Gad said.

“The stimulation of the spinal cord acts like a hearing aid, allowing networks of neurons below the injury to communicate with the brain.”

The research disproves a theory that only recently injured patients might benefit from the treatment.

All six participants had chronic and severe paralysis for more than one year and some for more than 10 years, but the study found spinal cord networks in patients with severe spinal cord injuries remain and can to be re-taught how to work.

Print

Print