Microplastics found in SA food

Microplastics are finding their way into the food chain.

Microplastics are finding their way into the food chain.

Broken-down microplastics have been found in variable concentrations in blue mussels and water within the intertidal zone at some of southern Australia’s most popular and more remote beaches.

Researchers warn that this means microplastics are now finding their way into human food supplies – including wild-caught and ocean-farmed fish and seafood sourced from the once pristine Southern Ocean and gulf waters of South Australia.

“Our findings shed light on the urgent need to prevent microplastic pollution by working with the communities, industries and government to protect these fragile marine systems,” says Professor Karen Burke da Silva, lead author of a new study on the matter.

Her Flinders University research team has sampled varying levels of microplastics on 10 popular beaches across South Australia, from Coffin Bay and Port Lincoln on the West Coast to Point Lowly and Whyalla on the Spencer Gulf, to Adelaide metropolitan beaches along with Victor Harbour, Robe and Kangaroo Island.

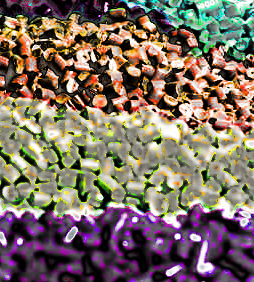

“Low to medium levels of microplastics less than 5mm in size) measured in the common blue mussel (Mytilus spp.), a filter feeder affected by ecosystem conditions, were measured to analyse the main kinds of pollution affecting the environment, and single-use plastic was the main offender,” Professor Burke da Silva says.

Microplastics are ubiquitous in the marine environment and tend to be more abundant in mussel samples near larger towns and cities, with levels four times higher at Semaphore Beach compared to more remote Ceduna on Eyre Peninsula.

Trillions of microplastic particles exist in the world’s oceans, with the highest concentrations recently found in the shallow sea floor sediment off Naifaru in the Maldives (at 278 particles kg -1 ) and lowest reported in the surface waters of the Antarctic Southern Ocean (3.1 x 10-2 particles per m3 ).

Microplastic concentration in the SA intertidal water was found to be low to moderate (mean = 8.21 particles l−1 ± 4.91) relative to global levels and microplastic abundance in mussels (mean = 3.58 ± 8.18 particles individual−1) – within the range also reported globally.

Plastic types include polyamide (PA), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), acrylic resin, polyethyleneterephthalate (PET) and cellulose, which suggests both synthetic and semi-synthetic particles from single-use, short-life cycle products, fabrics, ropes and cordage from the fishing industry.

“The areas examined include some biodiversity hotspots of global significance – including the breeding ground of the Great Cuttlefish in the Northern Spencer Gulf and marine ecosystems more diverse than the Great Barrier Reef (such as Coffin Bay), so cleanup and prevention measures are long overdue,” says Professor Burke da Silva.

“Apart from the harvesting of blue mussels, we also need to consider the impact of microplastic particles entering other parts of the human food chain with microplastic pollution expected to increase in the future.”

Print

Print