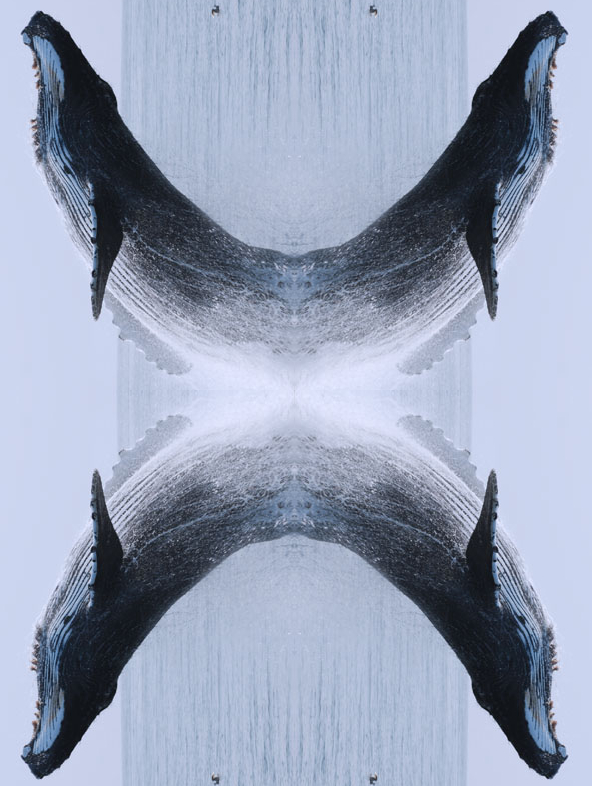

Humpback uptick brings reclassification call

Studies on the recovery of Australia’s humpback whale populations have revealed that they are increasing at a remarkable rate, among the highest documented worldwide.

Studies on the recovery of Australia’s humpback whale populations have revealed that they are increasing at a remarkable rate, among the highest documented worldwide.

Experts have even suggested removing the whale populations from the threatened species list.

“As of 2012, scientists determined that humpback whales on the west coast increased at a rate of nine per cent a year and on the east coast at a rate of 10 per cent a year,” researcher Professor Lars Bejder from Murdoch University says.

“The west coast population had recovered to approximately 90 per cent of their known pre-whaling numbers.

“Similarly the east coast population recovered to 63 per cent of its known pre-whaling population.”

Prof Bejder says the iconic humpback whales of Australia have become a symbol of hope and optimism for marine conservation, providing a unique opportunity to celebrate successful scientific management action that protects marine species.

The university has produced this discussion paper, gathering previously-collected and analysed data.

The research team presents an optimistic discussion proposing a revision of the conservation status for the humpback whales found in Australian waters.

They propose a revision of the status of humpback whales in Australia (currently listed as Threatened with a Vulnerable status) following the actions of several international governments and conservation organisations that have revised the status of other humpback whale populations experiencing similar growth.

“If humpback whales were removed from the Australian Threatened species list, the EPBC Act[http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc] would still protect them from significant impacts as a Matter of National Environmental Significance, as these whales are a migratory species,” Professor Bejder said.

“Beyond Australia, the International Whaling Committee manages the global moratorium on commercial whaling, which is essential for the humpback whales’ continued success.”

Fellow author Michelle Bejder said that one of the most beneficial consequences of removing humpbacks from the Threatened Species list would be the opportunity to reprioritise conservation funding to support species that are at a greater risk of extinction.

“Hopefully other animal species may be afforded a similar chance of recovery success to that of the humpback whales,” she said.

“Blue whale populations have been depleted greatly and remain endangered, while very little scientific data is available on Australian snubfin dolphins and Australian humpback dolphins.”

For the future, the paper’s authors say management efforts must now balance the need to maintain humpback whale recovery within a marine environment that is experiencing increased coastal development as well as rapid growth in industrial and exploration activities.

“Increased interactions with maritime users are likely to occur, including acoustic disturbance from noise, collisions with vessels, entanglements in fishing gear, habitat destruction from coastal development and cumulative interactions with the whale-watch industry,” Professor Bejder said.

“Adaptive management actions and new approaches to gain public support will be vital to maintain the growth and recovery of Australian humpback whales and prevent future population declines.”

Print

Print