Chinese pill check finds odd additions

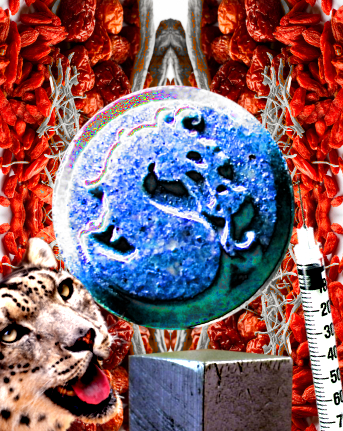

New research has found that some widely-available traditional Chinese medicines are laced with pharmaceuticals, heavy metals and even endangered animals.

New research has found that some widely-available traditional Chinese medicines are laced with pharmaceuticals, heavy metals and even endangered animals.

Traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) are sometime believed to be a more natural, herbal approach to curing ailments, but a study carried out by Curtin University, Murdoch University and the University of Adelaide found that a disturbing 90 per cent of 26 medicines tested were not fit for human consumption.

Around half contained illegal substances like toxic metals, prescription medications, stimulants and animal DNA.

Unsurprisingly, none of these were listed on the product's label.

TCMs are a multi-billion-dollar industry and previous studies have shown around 50 per cent of Australians have used them at some point.

While the most recent study did not disclose the brands of medicines it reviewed, it did state that all were purchased in Adelaide and were available nation-wide.

The researchers used highly-sensitive DNA sequencing, toxicology and heavy metal testing to assess the composition of the TCMs.

“Half of them have illegal ingredients in them, we've determined from DNA, half of them have got pharmaceuticals added to them that are clearly synthetic in nature and have not come from natural compounds,” Curtin University lead researcher Professor Michael Bunce told the ABC.

“Another proportion of them have heavy metals beyond the safe ingestion recommendations ... 90 per cent of them are really not fit for human consumption.”

Contamination by undisclosed pharmaceuticals was one of the most concerning findings, with over-the-counter drugs like paracetamol and ibuprofen detected, as well as steroids, the blood-thinner warfarin and even sildenafil, the main ingredient in Viagra.

“There definitely seems to be an element of deception in designing these things to have a specific outcome,” Murdoch University biochemist Dr Garth Maker told reporters.

“They may contain ephedrine, which will give a lot of people a buzz, and therefore they feel good and they think; ‘This is fantastic medicine, I should keep taking it’.”

But the presence of chemicals like strychnine - used as a rat poison and as a performance-enhancing drug – is clearly risky as well.

“Obviously if someone has been taking this for a very long time, they may have unwittingly exposed themselves to reasonably high levels of the poison strychnine,” Dr Maker said.

“If we don't know what's in them, it's very difficult to predict the interactions, and also [they can be] taken with other medications.

“That's obviously of great concern if they [have] been given to children, or pregnant women, the potential outcomes there are very serious.”

Professor Bunce commented on the bizarre finding of DNA of endangered species.

“One herbal medicine that's for sale had trace amounts of snow leopard DNA in it,” Professor Bunce said.

“We also found DNA from pit vipers, frogs and trace amounts of cat and dog DNA.”

It was unclear whether the animal products were meant to be primary ingredients, or were simply the result of poor manufacturing processes

Professor Bunce said all herbal medicines sold in Australia need Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) listing, but just 12 of the 26 products tested had been registered, and even they were deemed “low-risk”.

The remaining 14 had no TGA registration (and therefore should not be available to Australian consumers) but were still sold in commercial quantities.

Additionally, the TGA relies on the importers of such medicines to accurately list the ingredients.

Dr Maker said this honesty system is being exploited.

“We would hope there would be a rigorous screening procedure adopted by the TGA to actually monitor these compounds, medicines before they are actually put on sale,” said Dr Maker.

He believes the practise is widespread and increasing, something the National President of the Federation of Chinese Medicine Society of Australia Professor Tzi Chiang Lin denies.

“Of course, there are some people ... that are not that good and they might be making something not very nicely,” he said.

“[But you] cannot [put] blame on the whole profession, it will be one or two individuals. It may be one or two cases [that have] happened, but not many.

“The low-risk herbal medicines [are] already regulated very closely by [the] TGA, and they supervise very strictly the manufacturers in China.

“Over-regulation will mean trouble for the industry and [would not be] fair for the profession.”

Professor Lin said finding traces of heavy metal contamination is not actually that unusual, and probably came from the soil in which the ingredients were grown.

The findings have been published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, and the team says it will now look at up to 300 other widely-available herbal medicines.

Print

Print