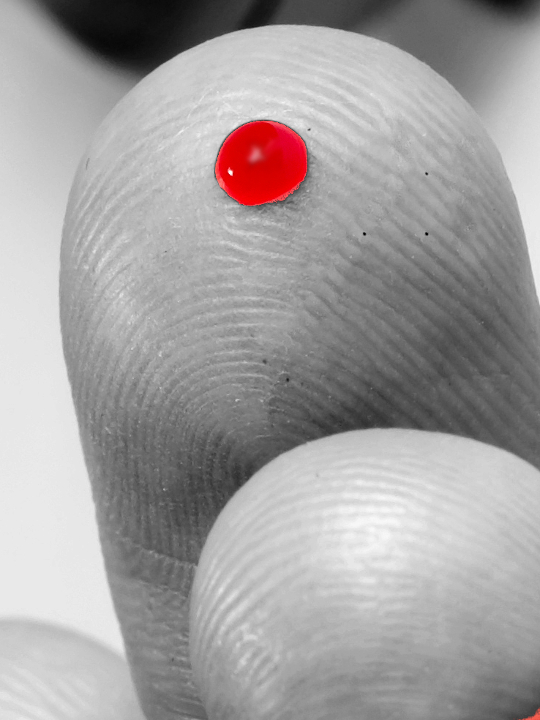

Blood test shows one drop ineffective

When it comes to drawing blood, most patients would want to lose as little as possible, but a new study suggests one drop may not be enough.

When it comes to drawing blood, most patients would want to lose as little as possible, but a new study suggests one drop may not be enough.

In the first study of its kind, bioengineers have found that results from a single drop of blood are highly variable, and as many as six to nine drops must be combined to achieve consistent results.

The study examined the variation between blood drops drawn from a single fingerprick.

They drew six successive 20-microlitre droplets of blood from 11 donors. As an additional test to determine whether minimum droplet size might also affect the results, they drew 10 successive 10-microlitre droplets from seven additional donors.

All droplets were drawn from the same fingerprick, and the researchers followed best practices in obtaining the droplets; the first drop was wiped away to remove contamination from disinfectants, and the finger was not squeezed or “milked”, which can lead to inaccurate results.

For experimental controls, they use venipuncture to draw tubes of blood from an arm vein.

Each 20-microlitre droplet was analysed with a standard hospital blood analyser for haemoglobin concentration, total WBC count, platelet count and three-part WBC differential; a test that measures the ratio of different types of white blood cells, including lymphocytes and granulocytes.

Each 10-microlitre droplet was tested for haemoglobin concentration with a popular point-of-care blood analyser used in many clinics and blood centres.

The researchers found that haemoglobin content, platelet count and WBC count each varied significantly from drop to drop.

“Some of the differences were surprising,” said Meaghan Bond, the student who spotted the inconsistency that started the whole project.

“For example, in some donors, the haemoglobin concentration changed by more than two grams per decilitre in the span of two successive drops of blood.”

The team found that averaging the results of the droplet tests could produce results that were on par with venous blood tests, but tests on six to nine drops blood were needed to achieve consistent results.

“Fingerprick blood tests can be accurate and they are an important tool for health care providers, particularly in point-of-care and low-resource settings,” Bond said.

“Our results show that people need to take care to administer fingerprick tests in a way that produces accurate results because accuracy in these tests is increasingly important for diagnosing conditions like anaemia, infections and sickle-cell anaemia, malaria, HIV and other diseases.”

Print

Print